‘Spreadsheets of empire’: red tape goes back 4,000 years, say scientists after Iraq finds | Archaeology

The red tape of the government bureaucracy extends for more than 4000 years, according to what is mentioned in the new cradle of civilizations in the world, a country of Mesopotamia.

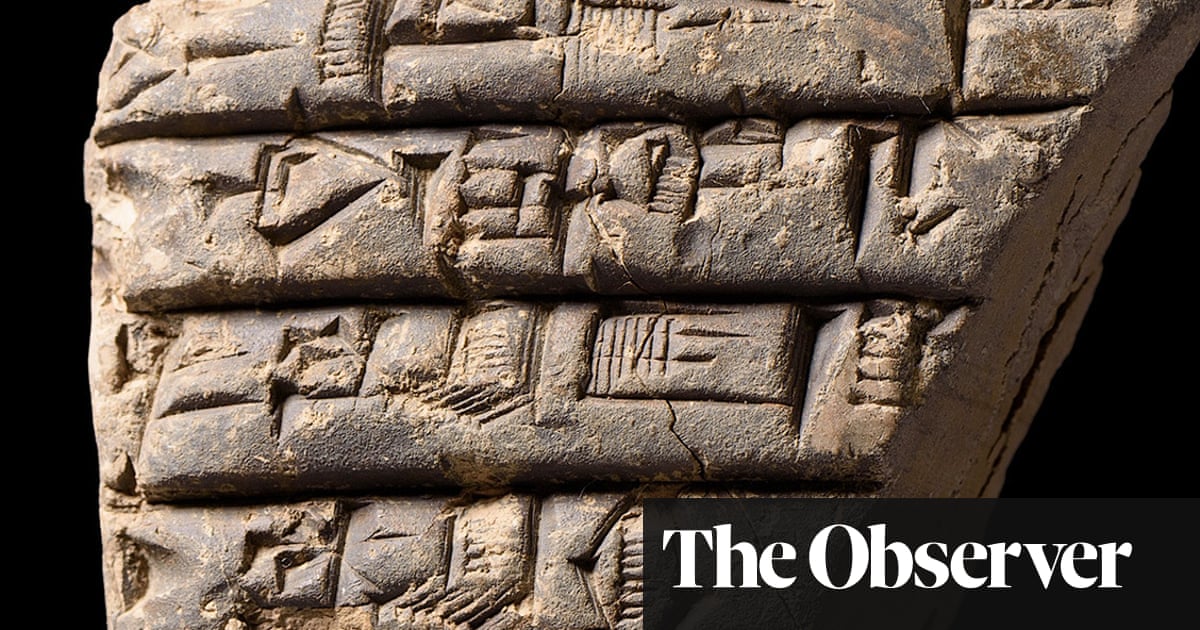

Hundreds of administrative tablets – the closest material guide to the first empire in the recorded history – was discovered by archaeologists from British Museum And Iraq. These texts are the details of government details and reveal a complex bureaucracy – the red tape of ancient civilization.

These were the government archives of the ancient Jersuus Somary site, Tilo in the modern era, while the city was under the control of the Akad family from 2300 to 2150bc.

“This is not different from Whittle,” said Sebastian Rei, Secretary of the British Museum in Mesopotamia and its director. Jerso Project. “These are the tables of the imperial data, the first material evidence of the first empire in the world – the real evidence of the empire’s control and how it has already succeeded.”

Jerso, one of the oldest cities in the world, was recorded in the third millennium BC as a haven for the Sumerian heroic Ningeru. Hundreds of hectares are covered at its peak, and it was among the independent Sumerian cities that were invaded by about 2300BC by King Sargon, a country of Mesopotamia. It originally came from the city of Okad, whose position is still unknown but is believed to be near modern Baghdad.

Ray said: “Sagon developed this new form of governance by conquering all Sumerian cities in Mesopotamia, and creating what most historians call the first empire in the world.” He added that even these recent excavations, information about this empire was limited to fragmented royal inscriptions and bomb, or later copies of Akkadian inscriptions “that cannot be relied upon.”

He said: “It is very important because, for the first time, we have concrete evidence – with artifacts on the site.” He was surprised by the details in those records: “They notice everything at all. If the sheep dies on the edge of the empire, they will be referred to. They are obsessed with bureaucracy.” The tablets, which contain cuneiform symbols, early writing system, state affairs, delivery and expenses, on everything from fish to domesticated animals, flour to barley, and textiles to gemstones.

Dana GOODBURN-BROWN, Pritish-MARICAN CONSERVATOR, cleanses tablets so that they can be copied. She said that the work is both strenuous and exciting: “People only think that things come out of the ground and seem to see them in the museum, but they do not do that.”

One tablet lists different goods: “250 grams of gold / 500 grams of silver / … dusy cows … / 30 liters of beer.” Even citizens’ names and professions, Ray said: “Women, men and children – we have names for everyone.

“Women carry important offices within the state. So we have great priests, for example, although it was a community to lead men. But the role of women was at least higher than many other societies, and it cannot be denied based on the evidence we have.”

The functions listed from stone stations ranges to the Temple ground. Ray said: “The ability to sweep the floor in which the gods and the great priest were very important,” said Ray.

The tablets are found at the location of a large archive building for the country, made of clay brick walls and divided into rooms or offices. Some tablets have architectural plans for buildings, field plans and channels.

The discoveries were achieved by archaeologists in the Girsu project, a cooperation between the British Museum and the Iraqi government’s heritage archeology council, funded by the Meditor Trust, a charity.

The site was originally dug in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and it was targeted by the wars after the two Gulf wars: “Either panels were almost either looted or removed without indifference from its archaeological situation, and therefore it was resolved. So it was very difficult to understand how the administration works.

“The main thing now is that we were able to properly dig it in its archaeological context. New discoveries have been preserved on the site, so in their original context, we can definitely say that we already have the first material evidence for imperial control in the world. This is completely new.”

The discoveries were sent to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad for more study, before a possible loan to the British Museum.

The Academic Empire lasted only about 150 years ago, and ended with a rebellion that had the independence of the city.